Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

My student apologized to me for voting for Donald Trump. He regretted it, he said, because he hurt me, and he never thought it would hurt someone like me.

The week before, he sat with me for almost an hour in my office, and we bonded over poverty. He told me how hard it was to be in college with rich friends, to be so different than them. He felt alone.

He’s talented, and I told him so. He’s funny, and aside from some trouble with comma splices, he’s a good writer. He told me that he’s majoring in business, but he wants to be a journalist. I encouraged him to do that.

He’s talented, and he’s sensitive, and he voted for Donald Trump.

***

Let me be clear: this isn’t an essay about bonding with someone who has opposing beliefs or about how people can defy stereotypes. My student is talented, and he’s sensitive, but he still voted for Donald Trump. My student hurt me, and he did it because he’s kind of stupid.

I don’t mean that in a cruel way. He’s stupid in that way that many 18-year-olds are, the way that I was stupid when I was 18. He’s full of good intentions, and he hopes for the best, even from the worst. He voted for Trump because he didn’t believe Trump really meant all those racist things. He hoped–and continues to hope–that Trump will be better than his disgusting rhetoric.

But he says that now he can see how Trump’s victory hurt me, and so many others, and, with that same hope, he hands me his apology.

And I hold this hopeful, well-intentioned apology, as I’ve held apologies before, and I just don’t know what the hell I’m supposed to do with it.

***

I live in Manayunk, Philadelphia, a predominantly White working class neighborhood at the edge of the city. When I walk to the bus stop each day, I see a large red pick-up truck; on its window is a decal of Calvin peeing on the name “Hillary.”

When I walk back home late at night, usually after teaching class, I worry someone in this White neighborhood will think I’m a criminal, simply for being in a White neighborhood (this wouldn’t be the first time it’s happened to me). They’ll call the cops. The cops will kill me.

Or maybe someone, anyone–or, I should say, anyone White–will see me, grab me, beat me. Kill me.

But now I wonder what my sorry student will think, if my corpse could mean anything to him. If somehow that will teach him a lesson, finally, about what an apology and good intentions are really worth.

***

The day I talk to my students about the election, I play them recordings of poets reading their poetry: Langston Hughes, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” Maya Angelou’s “And Still I Rise,” Eve Ewing’s “Epistle for the Dead and Dying,” Ross Gay’s “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude.”

And then I show them a small excerpt from a book, and I have a student read it out loud.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Misery is often the parent of the most affecting touches in poetry. Among the blacks is misery enough, God knowns, but no poetry.

I ask if anyone can identify it; they can’t. It’s Thomas Jefferson. I ask: what else did Jefferson write?

The Declaration of Independence, a student responds.

What does it mean, I ask, to live in a world where the government is founded by a man who believed that Black people didn’t possess the ability to write poetry? What does it mean when a man who owned and abused human bodies, what does it mean when his face is on your money, when you can take the train right now and stop off at Jefferson Memorial Hospital?

A Black student, one of two in my class, says simply, It means America wasn’t meant for us.

I don’t think we should look at Jefferson with our modern moral lens, a White student says. If, in a hundred years, everyone decides to stop eating meat, wouldn’t they think we’re monsters?

People aren’t meat, I tell him. People aren’t food. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with calling Jefferson a shitty person for enslaving human beings.

Another White student tries again: what if in the future, people think I’m a bad person for believing that there should be gender neutral bathrooms? Does that mean I’m morally wrong now?

He’s trying to appeal to my progressivism, but I tell him that that’s a straw man. A human life is not a bathroom.

We veer away from Jefferson, and return to Trump, to the election, to America at large, but later, as we wrap up our class discussion, I turn back to Jefferson: what is most notable about this quote?

I’m doing the thing where I have something in mind that I want the students to say. They don’t say it, so I do: he was fucking wrong.

He was fucking wrong, I say again. And you all know it, because you heard Black poetry at the beginning of class.

I stumble my way through an impassioned speech about the power of words, the persistence of poetry, even in times of suffering and oppression. Etc.

***

But this essay also isn’t about how poetry will save us. It hasn’t thus far. And I distrust anyone who salivates for art in the time of fascism. I’ve read all about what happened to Federico García Lorca. I know how that story ends.

Art is a wonderful, beautiful, powerful thing, but it isn’t a human life. It’s a bathroom. It’s meat. It’s good intention. That doesn’t stop a professor from telling me: take hope; punk rock will be really good under Trump.

***

I feel as though I’ve been saying I love you a lot lately, but maybe that’s not true. Maybe I simply feel it more acutely when I say it now, as though each time I say it to someone I love, I mean it desperately; my love is clawing at the air as it sinks into quicksand.

I feel as though I’ve been angry a lot; this is certainly true. I’m mad at Nazis, racists, Trump and his supporters, of course. This is a given. But there’s something particularly painful about the supposed allies who never see or hear you.I’m frustrated by White liberals, debating safety pins and economic woes; I’m frustrated by limp apologies and tears; I’m frustrated by neoliberal mourning.

They are so full of good intentions, but none of it makes me feel any safer.

This isn’t to say that there’s absolutely no comfort in good intentions. A classmate handed me a note the other day.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

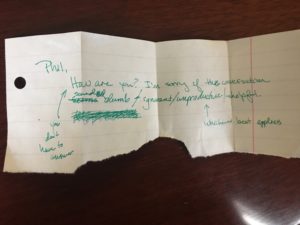

Phil,

How are you? I’m sorry if the conversation sounded dumb/unproductive/unhelpful. (Whichever best applies) (You don’t have to answer)

And I laughed, and it did make me feel a little better. I put it in my wallet as a reminder of good intentions. And I think of my student’s apology. And I think of poetry. I think of good intentions.

But I still feel like I’m going to die. I worry about my body becoming nothing more than a symbol, one that racists won’t give a shit about, one that White liberals will baptize in their tears. They’ll argue over my corpse and what it means; then I’ll be forgotten again, buried in good intentions and twisted straw men.

***

I’ve been trying to write this essay for days now, and I’m still not quite sure what it’s about. It seems since Trump’s election I’ve been reading about so many things, about so many silver linings, about so many good intentions. Yet the writers seem little concerned with the reality we face: we’re fucked.

We’re fucked, and they want to feel good about it. We’re fucked, and out of self-defense, out of privilege, they seek comfort and conclusions. We’re fucked, and they say: here’s how you can feel less fucked.

They make a mess, and then they want to feel comforted about the mess they made. But this isn’t about them. This is their mess, and I hope they never fully feel comforted about it. A mess is a problem; problems should cause discomfort. You should be uncomfortable.

And while it isn’t about them, maybe it’s about their mess. Or rather, it’s about us, the ones who find ourselves in this mess, the mess that wasn’t made for us, but the one we are nonetheless in.

Maybe this is about the student who approached me after class, who talked with me for almost an hour–not the regretful Trump supporter, but the young Black woman who said: America wasn’t made for us.

After class, she told me proudly that her grandmother tried to sue a descendent of Thomas Jefferson for reparations.

We talked. I thanked her for sitting through class, as I know it’s hard sometimes to sit through what White colleagues can say.

She said, I want to yell at them sometimes. But then I know they’ll think I’m just an Angry Black Woman. They probably already think that.

That’s how they get you, I tell her. If you’re silent, and you take it, then they’ll never stop ; if you’re angry and you say so, they stereotype you, and they’ll never stop. They try to keep you running.

She nods. I think I just lost hope, she says and laughs.

There’s always poetry, I tell her, for whatever that might be worth.

She smiles and tells me good night, and we part ways; her, back to her dorm, and me, back to my neighborhood, to the house where I will continue to live.